The mind-muscle connection has been on my mind for years. I first heard about it during my rehabilitation after a car accident when I was 17, and it sounded like nonsense at first.

I started going to the gym around five times a week which ended up being more than I’d ever done (cracking my PBs with every new week). Some say after an accident, you either stop what you were doing completely, or you get better than ever. Luckily I’d gone the latter way.

Eventually, I began to stagnate. I stopped getting the next-day soreness in my muscles — nor was I feeling that lovely pump in my arms and legs during a workout.

And it wasn’t until I found an article about this mind-muscle connection that I started to question whether it’s real or shallow bro-science.

What Is the Mind-Muscle Connection?

When people talk about the mind-muscle connection (MMC), then by definition, they refer to making a conscious and deliberate muscular action; the act of activating (and feeling) a muscle contract and not just moving the weight.

The ability to channel our focus into a single muscle or group of muscles relies on reasonable neuromuscular control and proprioception. This is why you can ask a novice lifter to flex their lats (in which 90 percent of people will look at you with absolute confusion), whereas a seasoned lifter of the ironclad will poetically orchestrate the individual segments of their fibres to show you what may look like wings under their arms.

Electromyography (EMG) studies found that when individuals focus on specific muscles before performing an exercise, they call upon a higher percentage of their fibres and fewer accessory fibres. This suggests that with resistance training and a sharper focus on the muscles you’re working on, your body can use more of that muscle to produce more force during your lift.

T-Nation conducted an EMG study in 2014 to assess the mind-muscle connection by measuring muscle activation during a selection of upper and lower body lifts. The goal was to maximise muscle tension and metabolic stress while steering concentration away from particular muscle groups, including the glutes.

Participants used “light” loads to aid their focus, and the results found solid evidence of a mind-muscle connection; T-Nation stated that glute activation increased from 6% to 38% of maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) when the individual focused on “steering” neuromuscular drive to their glutes.

Based on the experiment, advanced lifters seem capable of channelling tension to and away from muscles with lighter loads, which supports the idea of a mind-muscle connection.

Further, a 2012 study by Benjamin Synder and Wesley Fry revealed that verbal technique instruction could steer muscle activation during light loads (but not during heavy loads). A report by Science Daily also concluded that a sound MMC increases activation, helps with hypertrophy, and improves a beginner’s awareness of form. But they also found contrasting results, as focusing on external effects (the movement of a barbell) helps us lift more economically and with less effort.

So, here’s what you need to know:

The mind-muscle connection is real.

A good workout exercise is equally mental as it is physical.

Conscious efforts to activate a muscle before and between your set and visualising its appearance during a lift will help build a stronger connection.

Bodybuilders like Kai Green and the Hodge Twins have long lived by the mind-muscle connection. In one of my first ever days at the gym, this skyscraper of an eastern European man came to while I was doing tricep curls at a machine and automatically started coaching me on how to get a better ‘feel’ during the movement. His European accent was as strong as he looked, which only made him sound more convincing. I was a wimpy kid at the time who knew nothing about lifting, so any help I could get was valuable.

And he was right.

When I followed his tips, I felt a much better pump in my triceps—which was also terrible as it made the workout more painful.

I still follow his advice today, eight years later.

The Science Behind It

Scientifically — and in reality — your mind-muscle connection is easy to learn and improve on. Your brain and nervous system create relationships with your target muscle fibres that can be called upon to produce more force during your lift. In contrast, the accessory muscles are not innervated to the same degree.

Strength coaches and physical therapists believe that if an exercise is performed with good form, the right muscles will automatically do the job. And so it’s not necessary, or even possible, for the lifter to mentally alter their MMC.

Which side do you think is right? Does our load, cadence and form dictate muscle activation? Or can we mindfully “steer” neural drive towards or away from specific muscles by focusing on them?

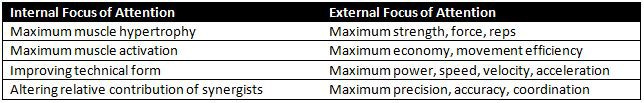

Below is a graph by Bret Contreras, one of the most reputable researchers and coaches for glute training. Here’s what he says about focusing internally versus externally:

Making Your Mind Work for Your Muscle

There are two specific training methods I promote for all beginners and most athletes I’ve worked with:

Tempo work

Isometric holds

A physiotherapist I went to for knee pain taught me that isometric exercises are exceptional for people who are in an early recovery stage. Why? Because spending more time in the eccentric phase of a movement (and holding the muscles still) inflicts less stress on your joints and tendons than constantly lengthening and shortening your muscles. Higher demand is placed on the nervous system, leading to accelerated improvements in coordination and motor control.

For example, spending two to four seconds in the eccentric part of all lifts during your first month of training offers can benefit your strength, endurance and your all-important fatigue resistance.

Likewise, our brain—not our muscle—is responsible for “newbie gains”, in which a beginner can experience a stark increase in strength during the first few weeks of a well-planned resistance programme.

Ideally, a fitness programme should account for the musculoskeletal and neurological components of resistance training. That includes primer sets to fire up your central nervous system during the warm-up and then isometric contractions (3–5 seconds) in a muscle’s fully shortened position to improve readiness.

Lastly, slow eccentric movements can improve your coordination, innervation, and muscular control whilst helping you target the right stimulus for muscle hypertrophy (through microdamage and cellular swelling).

Final Thoughts

The mind-muscle connection exists, but your form is where it counts. A simple observation from the outside doesn’t ultimately tell you what’s going on under the hood. For example, you can extend the hips and still barely activate your glutes during a back extension exercise. So it still matters to have good awareness to perform a lift correctly.

The literature shows that an external focus of attention (focusing on the outside of the body) will demonstrate good strength, endurance and accuracy. Beyond this, our MMC isn’t fake science plucked out of the air by someone; it can influence our neuromuscular dynamics during resistance training.

Consider exploring the methods below to help you strengthen your mind-muscle connection:

Try “loadless training”, whereby you practice flexing a muscle independently (like bodybuilders do when they pose) to enhance the strength of a muscle and its connective tissue.

Do low-load activation work before heavy strength training or between heavier sets.

Do heavy strength work with an external focus of attention (form). But afterwards, perform lighter work with an internal focus of attention — concentrating and activating target muscles.

Add slow tempo (eccentric-focused) and isometric (non-moving) movements to your workout.